Water Monitoring

In some of my previous posts, I talked about my journey towards monitoring every aspect of my home. For a long time now I’ve been measuring temperatures, electricity and gas usage, solar power and more. One area that has been on my target list from the start was our water usage - not least because a few years ago we had a leak that went undetected until it became a fairly significant problem. Recently while my plumber was doing our annual gas boiler service I asked him to fit a water meter which has allowed me to finally start tracking this data.

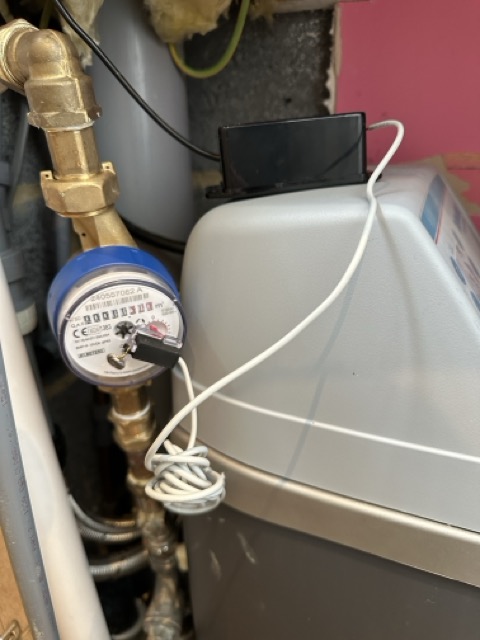

The key discovery that allowed me to do this was that you can get “pulsed” water meters (I used this model from B-Meters). They come preequipped with an inductive reader, and have a couple of wires you can connect to that receive a pulse for every litre of water used. Installing the meter was relatively straightforward for my plumber, despite the cramped space he had available.

I purchased a Raspberry Pi Pico W as it is easy to connect up the external devices, has WI-FI and runs a version of Python called MicroPython. I’m not the best at the physical side of builds, and my code is much neater than my wiring. I used a couple of alligator clips to link the meter wires to the Pico, and I put it all in a case to protect it.

The picozero library has a function specifically designed to count the number of pulses on a GPIO pin, so counting pulses is as simple as:

import picozero

PULSES = 0

def count_pulses():

global PULSES

PULSES += 1

switch = picozero.Switch(13, True, 0.1)

switch.when_activated = count_pulses

The key line is here is picozero.Switch(13, True, 0.1). The reason we’re using a Switch here is that the water meter has a switch that is

magnetically closed each time the meter reads a litre of water. The parameters are saying that we’ve connected it to GPIO pin 13, that we

want to use a pull-up switch, and that we want a debounce time of 0.1 seconds. You can use any general-purpose GPIO pin (a diagram can be found

here), just make sure to connect one wire to a GND (ground) pin and update the

number to reflect the pin you connected to. One problem that stumped me for longer than I would like to admit is that the pin identifiers on

the board don’t match the GPIO pin identifiers. Make sure you map the physical pin you’re using to the correct GPIO id.

I’m not going to go into the difference between pull-up and pull-down switches. For a circuit as simple as this the built-in pull-up/pull-down resistors are sufficient, and I’m not aware of any practical difference between the two options. Please do your own research before wiring your circuit up to avoid frying your Pico!

Lastly, the debounce time needs to be set to a balance between the maximum expected pulse rate, and how long it takes for the switch to settle to a solid value. With a switch that is physically moving it can take a short amount of time before it stabilises, and if you read it too frequently you will see it flip between on and off causing you to count pulses that aren’t real. In my use case, a pulse every 0.1 seconds would work out to 36,000 litres of water every hour. The highest rate I’ve seen is just under 1000L/h, so this is well above the expected max, and seems to be long enough to avoid counting phantom pulses. You might need to experiment to find the sweet spot for your situation.

Once you have a counter variable, you need to expose the value to Prometheus through an HTTP end-point. Since we expect this to only be accessed by Prometheus, I decided to skip most of the HTTP spec and return just enough for the metric scraping to work.

wlan = network.WLAN(network.STA_IF)

wlan.active(True)

wlan.connect(WIFI_SSID, WIFI_PASSWORD)

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.bind(("", 80))

s.listen()

while True:

conn, addr = s.accept()

request = conn.recv(1024)

conn.sendall(

f"""HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/plain; charset=UTF-8; version=0.0.4

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

Connection: close

# HELP watermeter_count Total litres of water used.

# TYPE watermeter_count counter

watermeter_count {PULSES}

""")

The first block of code connects to the WIFI, then we open a socket to listen on port 80. In a loop we then accept an incoming connection, read but discard the body of the request (so whatever path and HTTP verb you use, you’ll get the metrics back), and send a preformatted response with just the count of the pulses substituted in.

You can find the code, plus a bit of extra code for error handling and reporting via Sentry.io on GitHub.

To finish, here is a screenshot of my Grafana dashboard showing several different ways of visualising the data. The cost is calculated by another application I have running, which uses the Prometheus metric and the known cost per litre (plus a standing charge) to work out how much our water usage has cost me.

Comments